June 2, 2022

How We Brought Ethnic Studies to My High School

By Lisa Herforth-Hebbert

Students of color shouldn’t have to wait until college to learn about their histories.

Two summers ago, I was going through old binders when I came across a worksheet from my fifth-grade social studies unit on Christopher Columbus. A chart took up most of the page, dividing it into two sections: one for the pros and one for the cons of Columbus’s colonizing voyages. My thick, slanted, 10-year-old writing was clustered on the “cons” side, where I listed five negatives, including “Christopher Columbus put the Taínos into enslavement and if they could not give him gold they were executed.” I wrote just one positive: that “he discovered most of Central America,” which, of course, is not true.

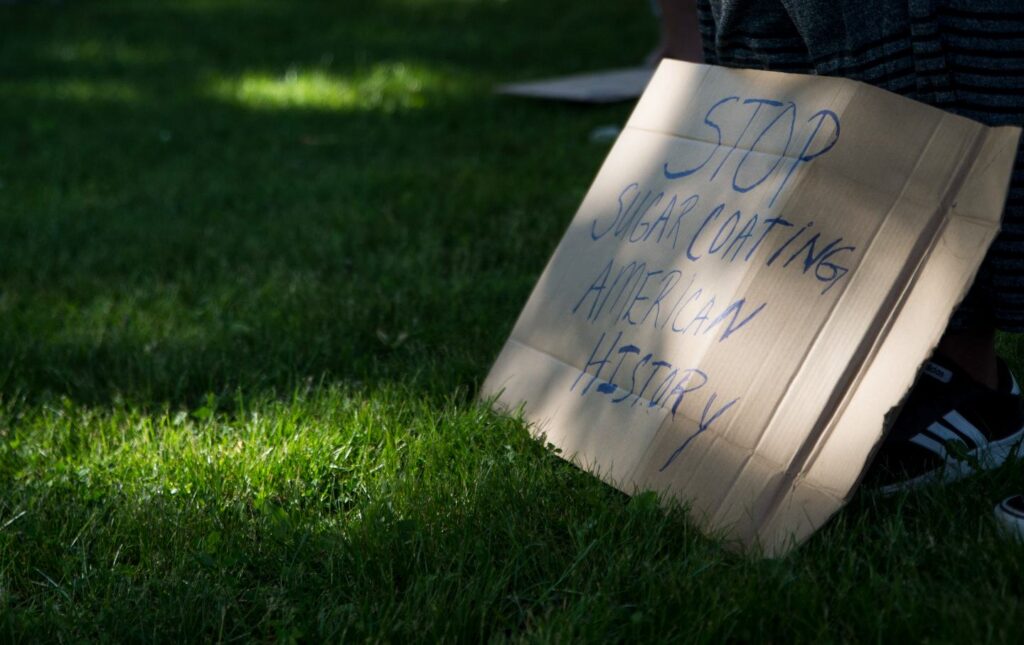

As I read over my answers more than 10 years later, I was deeply disturbed at the implicit judgement that the material and intellectual enrichment of European nations deserved to be considered a “pro” when it came at the expense of the genocide of Indigenous people. I sat on the floor, surrounded by these worn pages and memories, and felt the hollowness of the lack of ethnic studies in my primary education.

The worksheet became both a tangible and symbolic reminder of my own painful experience with Eurocentric textbooks and curricula as I began organizing with a coalition demanding a mandatory ethnic studies course at my former high school. I went to Menlo-Atherton (M-A), a majority POC high school in Northern California, where we were required to take European history to graduate. No class centered the experiences, perspectives, or histories of people of color. In my high school courses, I began to internalize the notion that my own cultural histories—Latin American and Latinx histories—were not academic.

Read full article.